Before we dive into the story of the film and how it came to be a classic sports movie, we invite you to consider some of our favorite sports betting sites. There you can bet on major sporting events, but also on which films will be the next to win Academy Awards and follow in the sprinting footsteps of Chariots of Fire.

Filmmakers’ Reluctance to Embrace the Olympics

Prior to the box-office success of Chariots of Fire, 1969’s Downhill Racer, with a stellar cast featuring Robert Redford and Gene Hackman, was probably the best known and most successful Olympic-themed movie. But, as celebrated film critic Roger Ebert described it at the time: “Downhill Racer is the best movie ever made about sports without really being about sports at all.”

The potential for an Olympic blockbuster was always there. After all, subject matter was plentiful. Jesse Owens quest to become a gold medal winner whilst facing-off against Adolf Hitler’s vision of Aryan supremacy at the 1936 Olympics should have been amongst the first feature films. It was not depicted on the silver screen until 2016.

The devastating violence at the 1972 Munich Olympics never got a worthy portrayal until Steven Spielberg’s suspense thriller Munich was released in 2005. Despite five nominations, that film didn’t win an Oscar at the Academy Awards.

In more recent times, movies with the Olympic Games at their core have adopted more of a comical formula to entertain viewers. 2016’s biographical Eddie the Eagle and 2017’s I, Tonya are two prime examples.

How Chariots of Fire Broke the Mold

It is often said, if there was no Rain Man there would have never been a Forrest Gump. Autism was taboo before Rain Man. Likewise; the Olympic Games was seemingly off limits before Chariots of Fire opened the floodgates.

But what made the 1981 film such a huge success and so popular even today? As a period-drama, baring the absence of en-vogue drone shots, the movie appears to have aged very well. That is a sizeable positive.

Similarly, a storyline that highlights antisemitism and class bias resonate with so many people even today. These were Harold Abrahams’s reasons to race.

The decision of Eric Liddell, the film’s second decisive character, to run for God and put the Almighty ahead of his country when choosing not to run on a Sunday, evokes admiration from all who watch this 124-minute story unfold.

Then there is the Chariots of Fire soundtrack. Three-and-a-half minutes of brilliance recorded by Greek musician Vangelis. Not since Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells Exorcist theme-tune in 1973 had a musical score fit a film so well. Few have done so since.

Amazing Chariots of Fire Facts

Unquestionably Chariots of Fire is a wonderful movie. Four Oscars, a Golden Globe, three BAFTA’s and a raft of other distinctions serve to verify that statement. So, over 40 years since its original release, let’s look at some little known and amazing facts about one of Britain’s finest pieces of cinema.

Timing

Released in May 1981 the film did not coincide with an Olympic year. It is conceivable its opening would have been even better received if it had. However, in 1980 the USA, China, the Philippines, Chile, Argentina and Canada had all boycotted the Moscow Games due to the Soviet Union’s presence in Afghanistan.

Four years later, in a tit-for-tat action, the Soviet Union and its allies shunned the Los Angeles games. Clearly, this was not a great era for the Olympic movement.

Casting the Cast

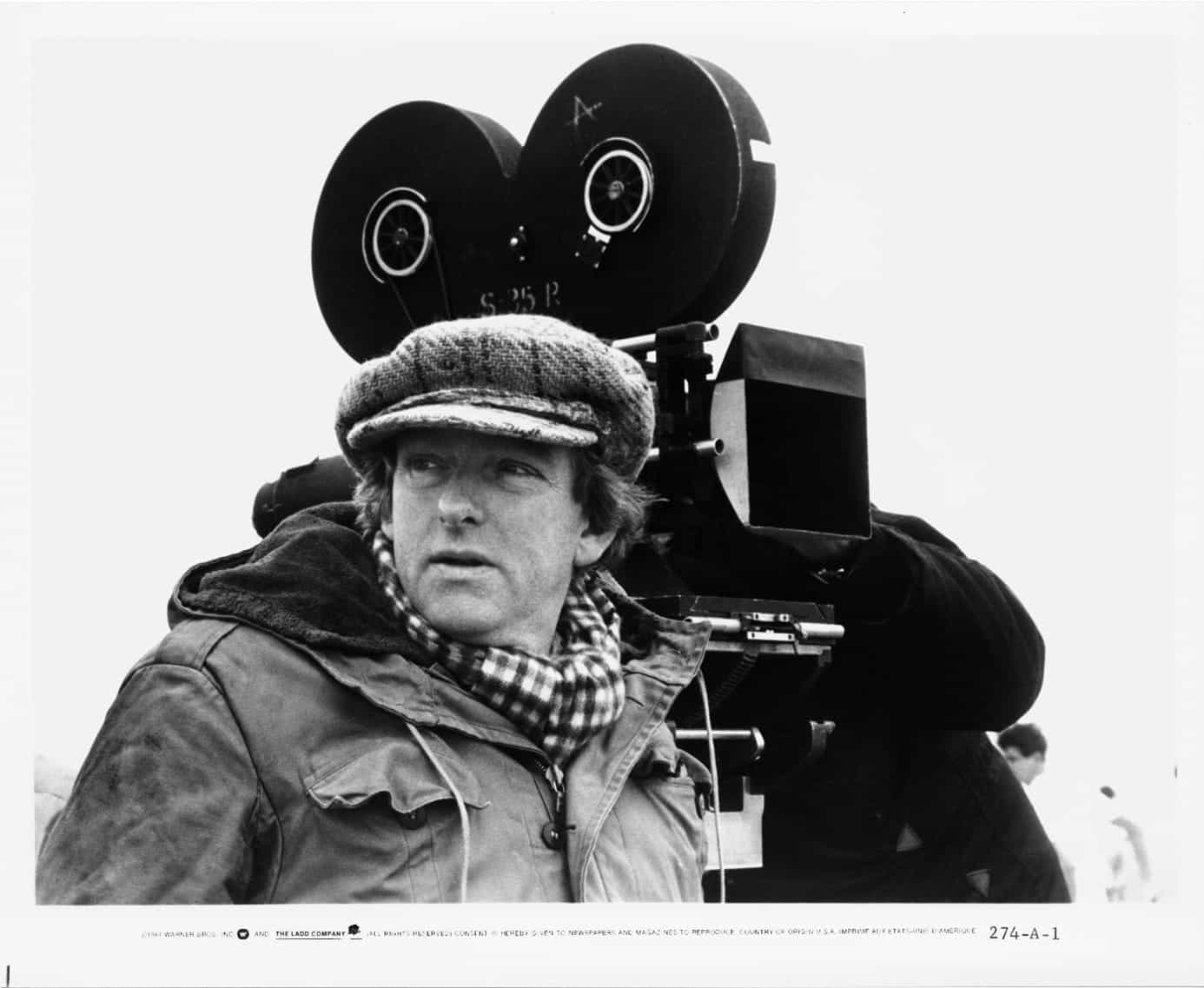

Director Hugh Hudson, who was making his directorial movie debut, chose to cast young unknown actors for the major parts in Chariots of Fire. Ian Charleson, who played Eric Liddell and Ben Cross, who portrayed Harold Abrahams, were both performing on the stage when chosen for the roles.

The older supporting cast was chosen from established veterans. Ian Holm was the best-known at the time. Portraying trainer Sam Mussabibi in Chariots of Fire, his previous role had been as Ash, the android programed with an evil agenda, in 1979’s smash-hit, Alien. At the insistence of 20th Century Fox – keen to widen the film’s potential audience – two small parts were given to American actors. Brad Davis (best known for a part in Midnight Express) and Dennis Christopher (Breaking Away) played American runners, Jackson Scholz and Charlie Paddock.

Opening Scene

After conceiving the movie, producer David Puttnam met Harold Abrahams and the 78-year-old agreed to offer his advice on the screenplay. They only met twice; their third encounter was at a memorial service held for Abrahams in London. Because of this, the film is bookended with a reenactment of that memorial service.

Extras

Actor Kenneth Branagh, comedian Ruby Wax, future England cricketer Derek Pringle and the multi-talented Stephen Fry were amongst the yet-to-be-discovered extras in the movie. Branagh also worked as a gofer on the set.

Filming Locations

Merseyside and parts of Scotland were the two filming locations for Chariots of Fire. It was the Oval Sports Centre located in Bebington in Merseyside which was used to depict Paris’ Olympic Stadium.

Scotland’s St Andrews Golf Course portray scenes said to be outside the Carlton Hotel in Broadstairs, Kent. Furthermore, West Sands, situated opposite St Andrews 18th hole, doubled for Broadstairs Beach which featured in the iconic opening running sequence. Most of the white-clad runners behind the lead actors in this training scene were St. Andrews golf caddies.

Cuts & Rating

40 minutes of footage were cut from the final movie at the insistence of Twentieth Century Fox studios. For American viewers, that included the axing of a brief cricket playing scene. However, for that audience, it was replaced with another scene featuring two First World War veterans who use an obscenity.

This was required to prevent the movie from being given a G-rating which was commonly associated with children’s films in America. The swear-word led to the film being classified as a PG.

Shoestring Budgeting

Chariots of Fire was a decisively low-budget production. It never showed as producer David Puttnam came up with ingenious ways of making ends meet.

For the Paris Olympics scene “we needed around 7,000 extras, and we didn’t have the money to pay 7,000 extras,” Puttnam explained in a 2021 interview with the Irish Times.

“So, I bought a car and a motorbike, advertised the fact they would be raffled on the day, one at lunchtime, the other at the end of the day, and anyone who turned up at 9.30am would get a ticket.

“Around 9.00am there was only a dribble of people, then we looked down towards Wirral train station and there was a long black line of people, in that last half-hour 6,800 people turned up!”

Regrettable Absence

The character Lord Andrew Lindsay (played by Nigel Havers) was actually based on Lord David Burghley who refused to allow his name to be used because of an inaccurate historical depiction in the film.

In reality there was never a Great Court Race at Trinity College in which Abrahams faced or beat Lord Burghley. Abrahams never once attempted the Great Court Run. But Burghley had sprinted in the courtyard race – which unlike the movie took place at midnight – within the 43.6 seconds it takes the Trinity clock to chime.

Cambridge Trinity College later expressed regret for not allowing film-makers to recreate the Great Court Race.

Burghley, who won a 400-meter Olympic gold at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, later announced he regretted his decision not to cooperate with the production. He died five months after the release of Chariots of Fire, aged 76.

Another to later announce regrets was Trinity College. At the eleventh hour, with actors and cameras ready to roll, the Cambridge college decided against allowing filmmakers to use their courtyard as a backdrop.

Eton College was ultimately used to depict Trinity in the Great Court Run scene. Within a few years, the Dean at the Cambridge college confessed that “it had been a great mistake not to cooperate with the making of this movie.”

Great Court Run

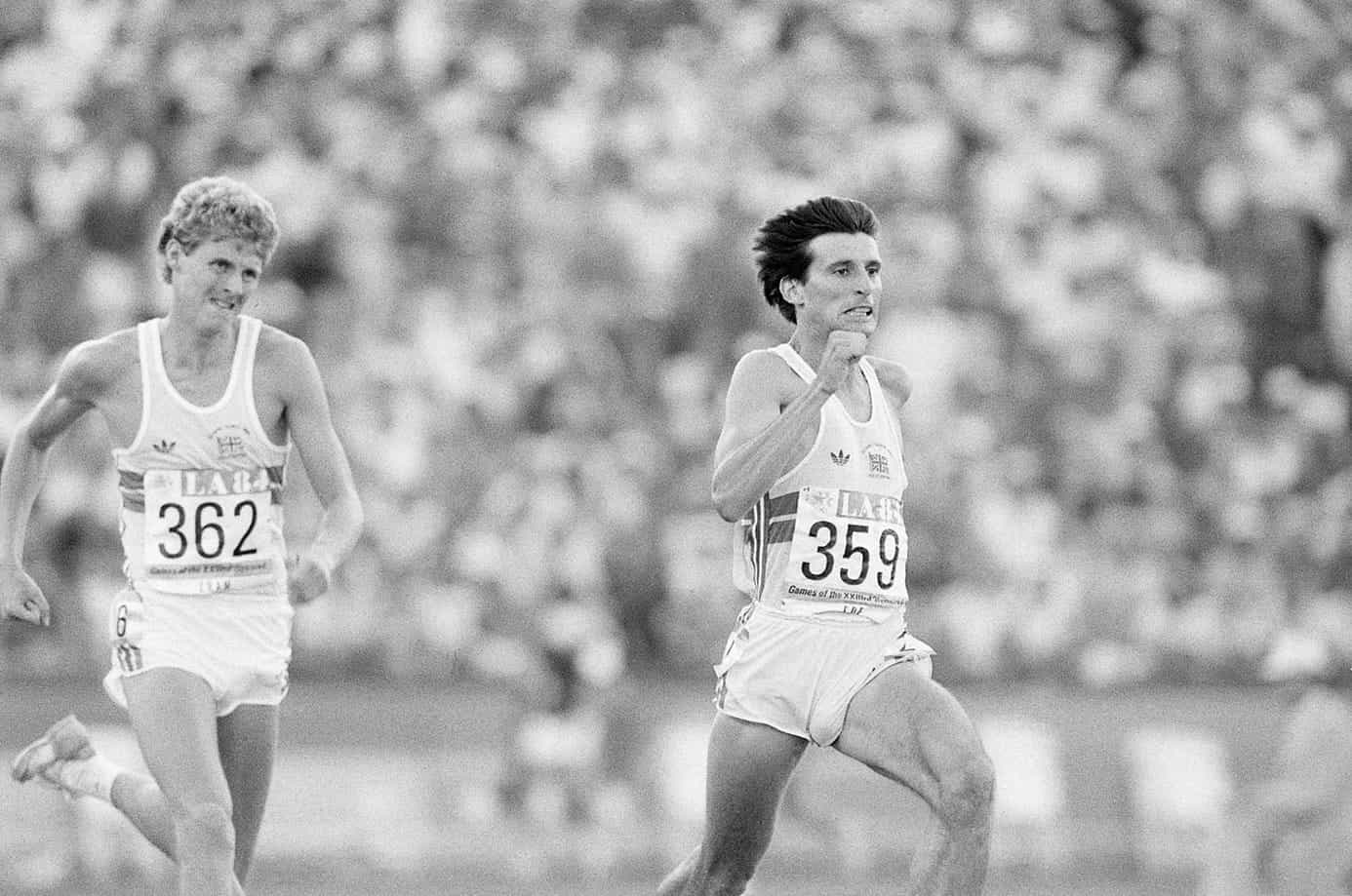

In 1988 Sebastian Coe and Steve Cram attempted the Great Court Run – a pivotal scene in Chariots of Fire – for charity. Both failed to beat the clock with Coe approximately 12 meters short of his finish line when the final clock stroke chimed.

Sebastian Coe beat Steve Cram in the final of the 1984 Olympic 1,500 meter contest. Four years later, when they attempted the Great Court Run, the result was the same.

Last Minute Music

Writer Colin Welland was stumped for a title for his draft of the movie. But a chance viewing of the BBC’s religious music series, Songs of Praise, led him to hear the words “Bring me my chariot of fire” during a recital of the hymn ‘Jerusalem’.

It gave him the film title he was looking for. Additionally, the hymn sung in church at Abrahams’ memorial service at both the beginning and end of the movie is ‘Jerusalem.’

Remarkably the iconic Chariots of Fire anthem came incredibly close to never being heard. “We had done the movie, mixed it, finished the film,” explained producer David Puttnam in the 2012 documentary The Real Chariots of Fire.

“And literally a few days later I was in a restaurant and the phone rang at the reception. I don’t know how Vangelis tracked me down, but he said I must see you. He drove round, halfway through our meal we went outside, he’s sat outside in his Rolls Royce. He showed me a cassette, he popped it in, we sat in the back and I can honestly say every hair on the back on my neck stood-up.” Amazingly Vangelis father had run for Greece in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Sadly, he had died shortly before Chariots of Fire and his son’s movie track was released.

Oscar Winner

In 1982, Chariots of Fire was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four of them. They were: 1981’s Best Original Score, Best Screenplay, Best Costume Design and the hallowed Best Picture.

This was the first non-American movie since Oliver in 1968 to win the Best Picture award and it beat off strong opposition from Raiders of the Lost Ark, Reds, Atlantic City and On Golden Pond.

Actor Ben Cross, playing Harold Abrahams, crosses the 100m winning line marginally ahead in a memorable scene from Chariots of Fire.

At the start of his acceptance speech for the Best Picture award producer David Puttnam thanked Dodi and Mohamed Al Fayed for “putting their money where his mouth was”. This was in reference to the father and son duo producing the seed money needed to get the Chariots of Fire project off the ground.

Beforehand, in 1979, Dodi Fayed – who perished alongside Princess Diana in the infamous 1997 Paris car accident – co-produced Breaking Glass which has since become a cult classic.

Factual Inaccuracies

In addition to Abrahams never contesting the Great Court Race at Trinity College, a big deviant from the true story’s facts is Eric Liddell being informed of his 100-meter heats taking place on a Sunday as he boarded a steamship for Paris.

Liddell had known of the Sunday date eight months in advance of his journey to the Olympics. He never wavered from his decision not to race in the 100-meters – the race that most suited to his talents.

Additionally, the Scotsman did not compete in the 4 × 100-meter relay or the 4 × 400-meter relay because both required him to run on a Sunday which was against his faith.

Medal Whereabouts

In 1992, Eric Liddell’s Olympic gold was gifted to Edinburgh University by his daughter. Liddell had attended the University and graduated from it with a Bachelor of Science degree after the Paris Olympics.

Harold Abrahams cut a strip of gold off his Olympic gold medal to make his brides wedding ring. Sadly, both the ring and his two 1924 Olympic medals were stolen sometime in the 1970s. But plenty of Abrahams’ medals and memorabilia do remain. In 1989 Mohamed Al-Fayed purchased about 30 of Abrahams’ medals, stopwatches and his Commander of the British Empire award presented by Queen Elizabeth II in 1957. The collection was put on display in Al-Fayed’s Harrods Department store later in 1989.