The Founder’s Message

For those who do not triumph at the Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, coined a phrase that has since dwarfed its official motto. He said: The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

First mentioned in a 1908 speech, the mission statement was not officially used until the opening ceremony of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games. Four years later, using a recording made by Pierre de Coubertin, his famous words were broadcast at the Berlin Olympics.

With World War II intervening, the next Summer Olympics were staged in 1948. Pierre de Coubertin had since died but his words and wisdom were displayed on the Empire Stadium’s scoreboard in London for all to see as the Olympic flame was lit.

Baron de Coubertin’s famous quote can be seen behind the US Team at the 1948 Olympics: ‘The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well’.

Indeed, most that came to conquer have failed. Champions have stood tall, and legends have been made, but the indelible moments? For many the memories of athletes that took their place on an Olympic podium step are matched – and even surpassed – by some others that did not.

The equal joy and pain that top level sport can bring is one of its greatest appeals. It is why billions of people around the world watch the Olympics, and it is why millions choose to bet on sports as well. We all wish to take part in some way in the challenge.

Here we have highlighted four athletes who, in demonstrating remarkable determination, bravery and courage, displayed the pure distilled spirit of the Olympic Games. A reminder: “…the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

John Stephen Akhwari

Tanzania sent four athletes to the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Neither of the country’s sprinters progressed to the final of their events. Their boxer, Titus Simba, was mauled in his only fight in the middleweight division.

In fairness, not much was expected of their other representative, John Stephen Akhwari, running in the marathon. But he was to deliver one of the most iconic moments of that year’s games.

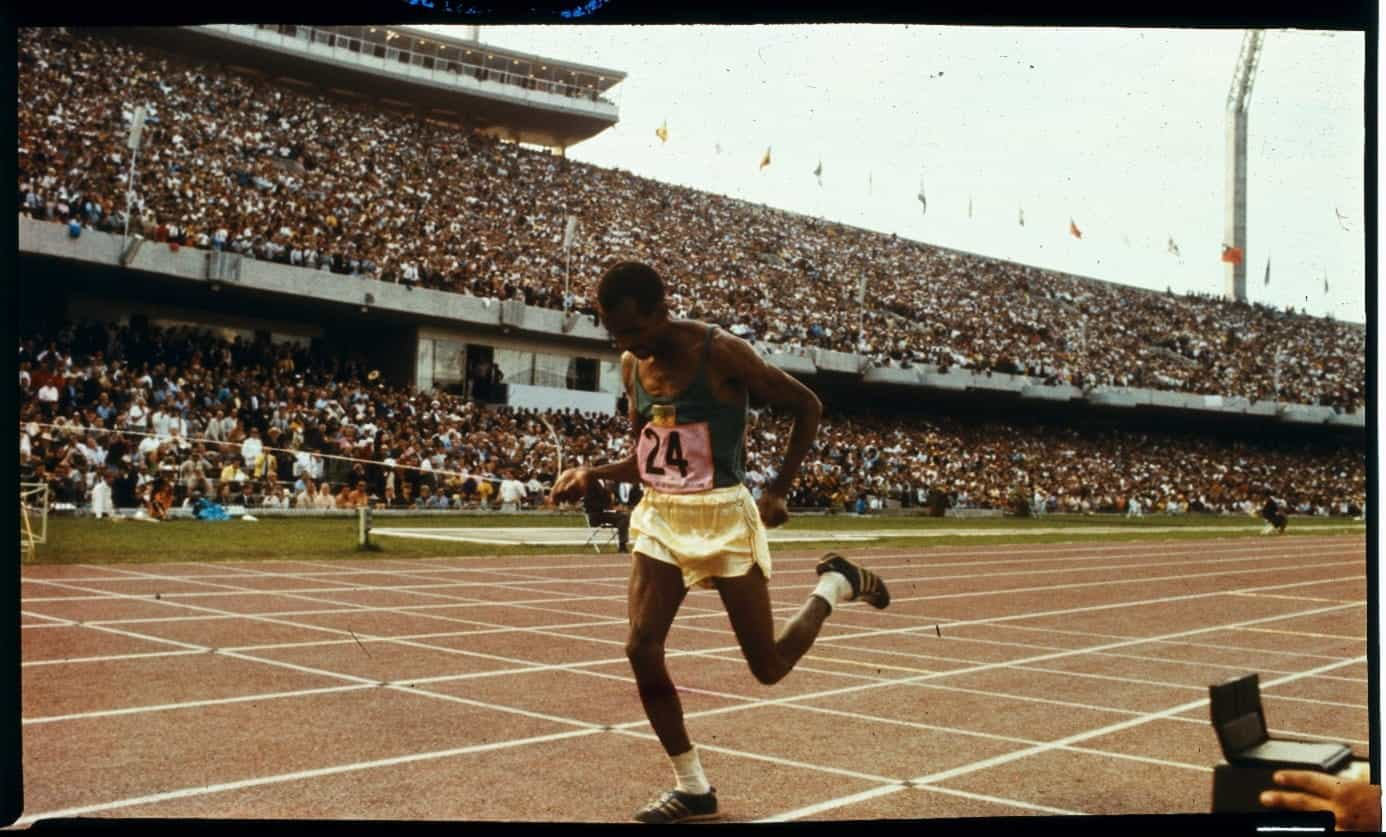

Ethiopia’s Mamo Wolde winning the 1968 Olympic Marathon gold. It was nightfall and he had been awarded his medal when John Stephen Akhwari finally entered the stadium.

The 1968 Olympic Marathon was a grueling contest. High altitude meant oxygen was in short supply. Of the 75 athletes who set out, only 57 competitors finished the race. John Stephen Akhwari was the 57th placed finisher.

Injured Mid-Race

Midway through the contest the 30-year-old suffered a bout of cramp and had also taken a fall. Jostling between rivals caused him to fall, sustaining a dislocated knee and a bad injury to his shoulder.

Roadside, a makeshift bandage was applied and despite crippling pain he continued to race. By the time the Tanzanian entered the Olympic stadium for the final 400-metres of his journey, it was nightfall.

Not only had the winner crossed the line more than an hour beforehand, but the victors had also been given their medals in the final trophy presentation of the games. It was the camera filming this awards ceremony that unexpectedly captured Akhwari’s titanic effort to finish the race.

When interviewed afterwards and asked why he continued running, he said: “My country did not send me 5,000 miles to start the race; they sent me 5,000 miles to finish the race.”

Kerri Strug Shrugs off Injury

The diminutive 18-year-old gymnast Kerri Strug became an American hero in 1996. Her part in that year’s gold-medal-winning women’s Olympic gymnastics team would have obviously given her fame and notoriety.

But it was her outstanding bravery that led her to pay a personal visit to President Bill Clinton, appear on prime-time television talk shows, make the cover of Sports Illustrated Magazine and to become an Olympic icon.

Vaulting for Victory

In a classic USA vs Russia Olympic confrontation in the woman’s gymnastic team event the destination of the gold medal was at a knife-edge. Strug had just sustained an injury to her ankle after a fall on landing from a vault.

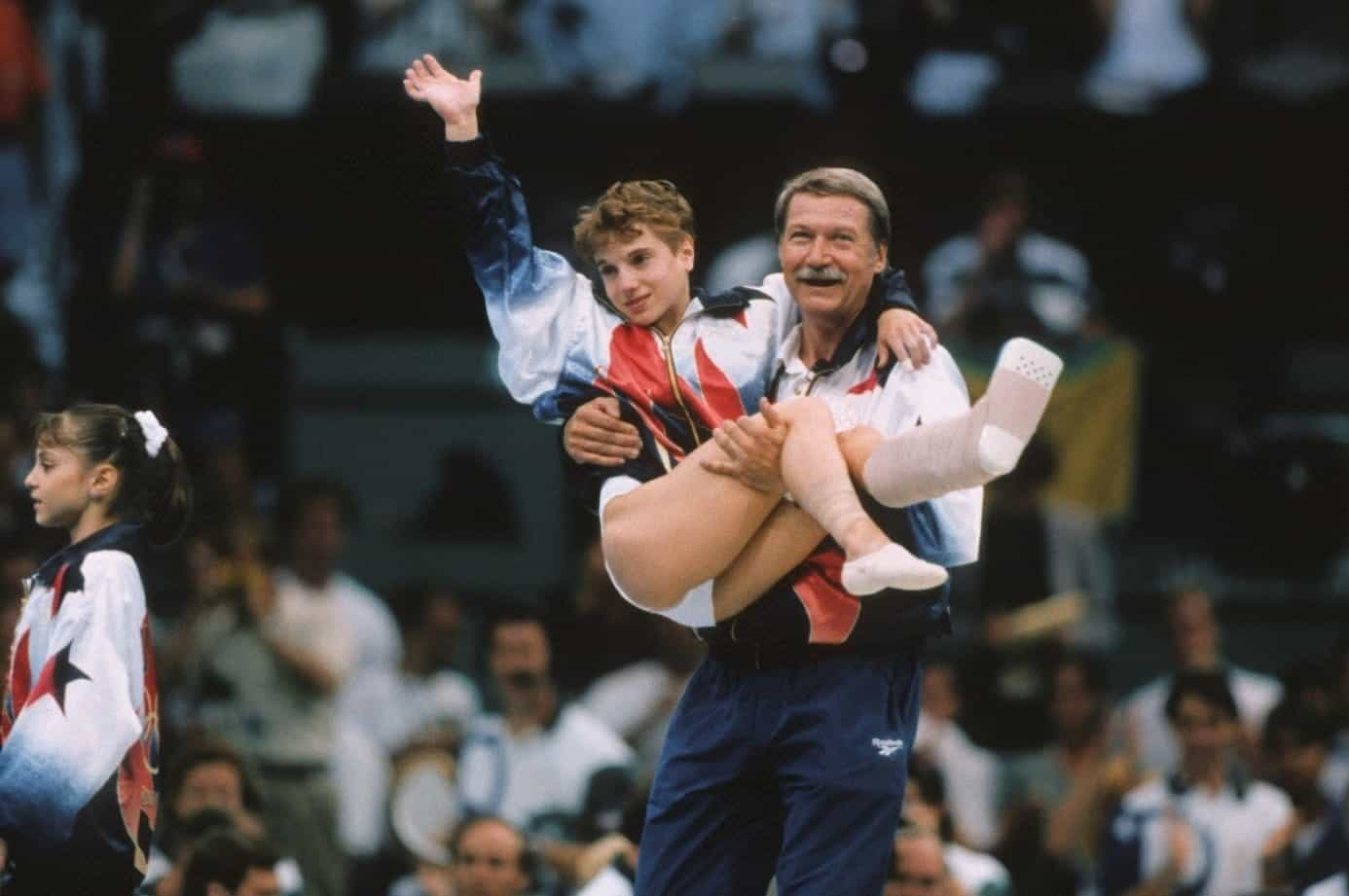

Kerri Strug is carried by her coach, Bela Karolyi, to the medal podium after she bravely took her final vault and her team, later nicknamed the Magnificent Seven, claimed gold.

However, despite her pain and discomfort – which transpired to be two torn ligaments – and after just a short interval she was asked to perform the vault one more time. “Kerri, we need you to go one more time. We need you one more time for the gold. You can do it, you better do it,” her coach Béla Károlyi was heard to say.

The injured gymnast made the final vault of the competition, successfully landing on both feet. But moments later she stood on just one foot and, after acknowledging the judges, she fell to the ground.

Carried from the landing platform, Strug’s coach later lifted her onto the medals podium. After collecting her gold medal, the teenager’s injuries were then treated in hospital. They dictated she was unable to take any further part in the games in which she had qualified for two more disciplines.

Derek Redmond’s Devastation

Just 90 seconds before the start of his 400-metre heat at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Derek Redmond accepted he had run out of time. Pain-killing injections into his Achilles tendon, applied on the morning of the race, had failed to work. He was forced to bow to the inevitable – he could not run.

During the intervening years between that sad day and Barcelona’s 1992 Summer Olympics, Redmond had undergone no less than eight operations to fix his injuries. However, aged 26, he was at his physical peak, he was not carrying any injuries and he had won gold at the previous year’s World Championships.

The 1992 British Summer Olympic team consisted of 371 athletes. The came home with five gold medals but Derek Redmond’s determination to cross the line despite injury was one of the biggest stories.

What could go wrong for him this time? Based on a 45.03-second heat win and a slightly faster but eased-down quarter-final success, it would appear very little. He was the fastest qualifier entering the semi-finals and a gold or silver medal looked like a very real prospect.

Disaster in a Snap-Second

But it went horribly wrong in his semi-final as Redmond, talking to the Financial Times in 2012, explained: “I was absolutely just flowing down the back straight. Nice and easy, no strain.” But he then heard a strange popping sound. “I thought it was a sound in the crowd, and I remember thinking to myself, come on Redmond concentrate.”

The sound had been Redmond’s hamstring snapping and strides later the athlete was on the floor with the field disappearing into the distance. “I thought, ‘If I get up now and start running, I will catch these guys.”

He did get up, he hobbled on. “I am going to finish regardless of what else is happening around me in the stadium and in the world,” he said to himself. Quickly supported by his father who appeared from the crowd, the athlete eventually limped over the line in tears with the realization his Olympic dreams were over.

Two years after the Barcelona Olympics Redmond was told by surgeons that he would never run again or represent his country in sport. He went on to play professional basketball for the Birmingham Bulls and now works as a motivational speaker.

Gabriella Andersen-Schiess Melts in the Heat

Remarkably the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics marked the first time the modern Olympics featured a woman’s marathon. The argument for not staging a woman’s marathon beforehand was its potential to be a health hazard.

It was a classic case of Murphy’s Law. When women finally got their chance to show 26 miles of tarmac pounding was not too much of a physical ask, the Californian climate conspired against them.

The 50 competitors from 28 countries should have had few issues completing the course. But temperatures in the high 80’s, and humidity in excess of 95%, meant six athletes would fail to finish. Ultimately, the field was well strung out at the finish. Over four minutes covered the first six home.

From Snow to Burning Sunlight

Amongst those to struggle, was 39-year-old Gabriela Andersen-Schiess. Being Swiss and working as a ski-instructor, high-temperatures were never going to favor her.

But antiquated rules that stipulated there could only be five water stations during the contest and her missing the fifth and final drinks station meant Andersen-Schiess became severely dehydrated toward the end of the race.

With a stiff right leg, limp left arm and walking in every direction apart from forwards, Gabriela Andersen-Schiess manged to cross the line in the 1984 Olympic Marathon.

Twenty minutes after the winner had crossed the finish line, Andersen-Scheiss staggered into the LA Colosseum. Suffering terribly from heat exhaustion, her muscles were not responding to instructions, they simply couldn’t.

Nevertheless, with a stiff right leg, limp left arm and walking in every direction apart from forwards, she stumbled her way around the 400-meter circuit. Her visually heart-breaking journey, before 100,000 spectators, took 5-minutes and 44-seconds.

When Andersen-Scheiss finally fell across the winning line medics were there to catch her. Thankfully she quickly recovered and instantly became an Olympic legend.